SPAB Scholars: Thatch, the Climate Crisis and the Chance to Bring Heritage Crafts Back From the Brink

Share on:

Lewis Hobbs, Architectural Assistant and 2023 SPAB Scholar, explores how a changing world has altered thatching in the UK, and what can be done to secure the future of this traditional craft.

The early summer sun warmed us as we hung from the thatch of the cottage on small ladders, tools in hand. As part of the Lethaby Scholarship we had been given the chance to learn about many crafts from the masters still practicing them, but not many came with a view such as this.

The clouds rolled over the Shropshire landscape as Alan Jones, a master thatcher out of Pembrokeshire, and his team talked us through the replacement of a ridge, how to redress a roof and all things thatch. Birds chirping, the sound of straw being pitched out behind us, the occasional rumble of cars, and the thud of the leggett (a flat headed paddle tool) accompanied our teaching.

These opportunities have been a key part of the Scholarship programme, immersing ourselves in one craft after another, so that we can not only understand the methods, materials, and tools, but also the challenges facing these trades today. It’s also about how we can come together to solve these challenges so that we can continue to look after these fantastic buildings well into the future.

Scholar Lewis Hobbs putting some of the ridge in place.

The risks to thatching

Sitting there in the evening, Alan talked of his craft, its history, its vernacular and regional differences, and its future from his viewpoint.

The way of life that supported the use of the entire crop, through food and roofing material, has changed and is no longer possible. With the modernisation of farming practices, straw has changed from the long heritage varieties perfect for thatch, to shorter types that are fast to grow and harvest. It is now harvested later for food, to reduce moisture content, and as such it is brittle, making it hard to find quality roofing materials.

Land and forest management changes mean coppiced hazel is less available. The global pressures of markets and conflict, for example in Ukraine, negatively impact the availability of spars for thatching.

Years ago, Alan grew his own crop and used it to produce bread, showing that food can be the ‘by-product’ of thatching materials (or vice versa) like it had been traditionally. This type of approach could be adopted to help support the industry if the demand was there.

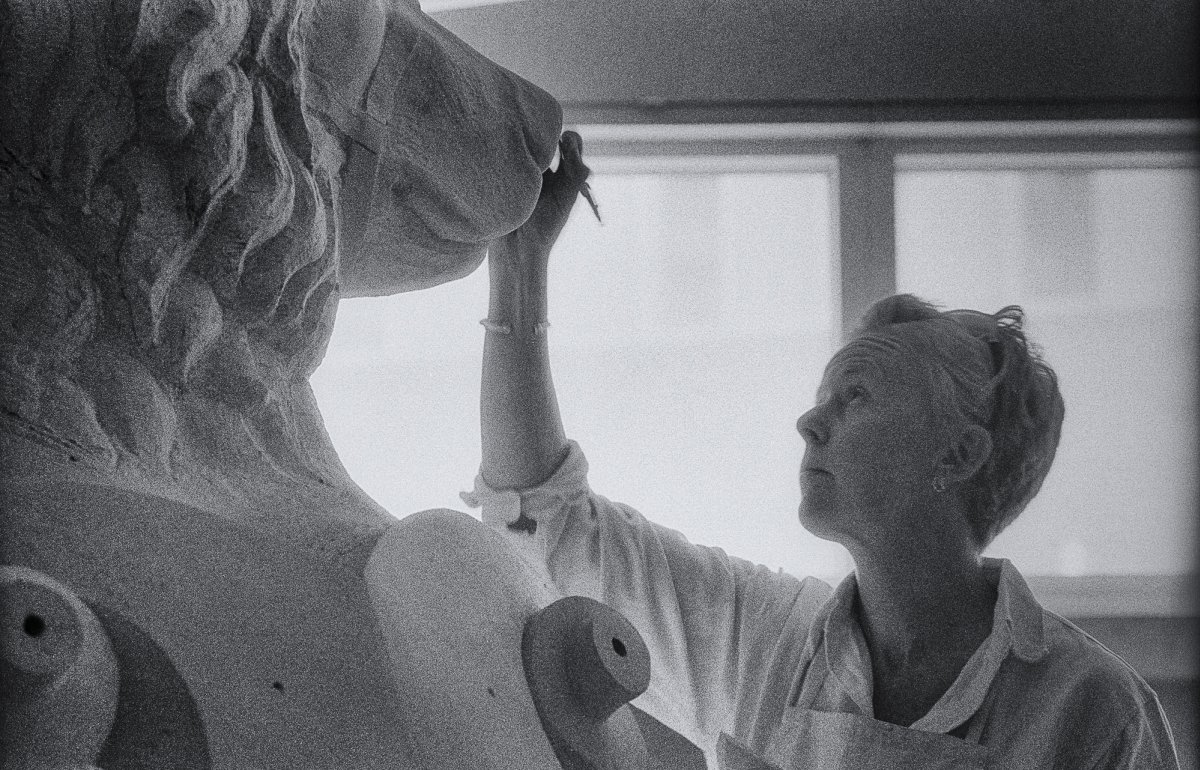

Scholar Laura Brain putting some of the ridge in place. Credit: Lewis Hobbs

Crafts at risk

The problems that affect thatching are not exclusive to one heritage craft, many that once were part of a spider-web of industries have had their ties broken by industrialisation and globalisation. What was once seen as progress has had a lasting impact on land management that will take time to reverse, although the climate emergency means there is now a renewed interest in sustainable materials and traditional or vernacular construction materials and methods.

More and more crafts are becoming ‘at risk’ as mechanisation overtakes the human touch. These are detailed in The Red List of Endangered Crafts, kept by Heritage Crafts. It sets out the category of risk for each craft (from extinct to currently viable), any professionals still practicing, and also the main issues impacting the crafts viability. Things like material supply chains, rising costs of materials and equipment, and loss of supporting ‘sub-crafts’ are all key factors.

Lewis learning how to pitch out the straw.

Future-proofing heritage crafts

For these crafts to survive, we need to bring people back to a more local way of thinking. If we can support locally grown straw for thatching, and English coppiced hazel for spars, then suddenly the availability and cost of these materials falls back into line. If specifiers can begin to reintroduce these vernacular materials and crafts into our work then the demand will increase and support these supply chains.

It requires a wholesale societal shift towards a more sustainable design ethos, but if our environment and our heritage crafts are to survive it is something that needs to be considered, and sooner rather than later. And, whilst we make this change from the bottom up, larger entities should be encouraging it from the top down so that we can meet in the middle before it is too late.

The renewed interest and support for heritage crafts has brought with it financial aid for training in these skills, although for many craft education centres it is too little too late. But this needs to be developed further if we’re going to re-establish the connections that have been severed to sub-crafts and their industries. The solution is not one for building conservation to take on alone, but the revolution needs to start somewhere -- so why not here? The desire and ability are there: it is time to capitalise on it.

Applications are open for the SPAB Scholarship 2024. The Scholarship is a unique training programme for early career architects, surveyors and engineers to gain the skills and knowledge they'll need to work with traditional buildings. Find out more and apply by Tuesday 31 October.

Sign up for our email newsletter

Get involved