World Architecture Day: The Evolution of the Architect

Share on:

Architects of the ancient world were not like the architects we know today. Author and architect Eleanor Jolliffe considers the emergence of the professional architect and the changing nature of the profession.

Knowledge about how we build has always been treated with reverence. In ancient Egypt, books of architectural plans and details were kept in closely guarded sacred books by Pharaohs; in medieval Europe the secrets of stone construction were protected by the masons’ guilds and during the building of Florence’s cathedral in Renaissance Italy, Brunelleschi charted a fractious relationship with masons over his refusal to divulge the technical construction details to his design.

Architects of the ancient world though, were not like the architects we know today. They were design specialists but often, also master sculptors, engineers, marine or military engineers or designers of public festivals. Indeed, the term ‘to architect’, is used by both Plato and Aristotle to describe civic and intellectual leadership, implying an application of knowledge in practical ways for the common good.

This breadth of skills didn’t change significantly with the fall of Rome. When European economies began to recover between the 11th and 14th centuries CE, the role of the architect reappears in the guise of the master mason. These multi-talented craftsmen-architects trained in the most prestigious building material of the time - stone - through an arduous series of apprentice and journeyman roles. Rarely literate, they nevertheless oversaw the workforce and solved complex structural problems, while developing the design of the building and occasionally picking up the chisel themselves for particularly complex or intricate work. Their knowledge continued to be treasured and passed down through the networks of masons’ lodges.

The impact of the Renaissance

By the time of the Italian Renaissance changes were taking place. Giorgio Vasari’s, The Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors and Architects, first published in 1550, demonstrates that increasingly architects were spending time studying ancient Roman texts on architecture and drawing and measuring ruined buildings. The recognition that architecture was a worthy pursuit for scholars led to a growing misconception across Europe that master masons were not sufficiently educated to carry out design.

Leon Battista Alberti went so far as to pronounce that, ‘the manual worker being no more than an instrument to the architect, who by sure and wonderful skill and method is able to complete his work’. In spite of this view, documentation reveals that Alberti still required significant support from his craftsmen in the detail of his designs. The intellectualising of Alberti and others led to a profound shift in the ownership of designs, from the artisanal view that - ‘it is mine because I made it’; to the intellectual standpoint - ‘it is mine because I designed it’.

The increasing distance between the architect and the artisans on site, led to further revolutions in architectural practice including, the rise of the architectural drawing. The drawing developed to become a comprehensive instruction document rather than a visual aide to support verbal instructions. Between the 1550s and 1750s in Italy, this shift becomes increasingly clear as the background of architects' changes from the majority starting their careers in the building crafts, to the majority emerging from the middle and upper classes with more formal liberal arts educations.

The design was no longer decided during the process of building as the emphasis shifted to the completion of the full design before construction started. By the end of the 16th century, we no longer see the architect perched on the scaffolding with chisel in hand. Instead, the profession is centred around the architectural office.

"By the end of the 16th century, we no longer see the architect perched on the scaffolding with chisel in hand. Instead, the profession is centred around the architectural office."

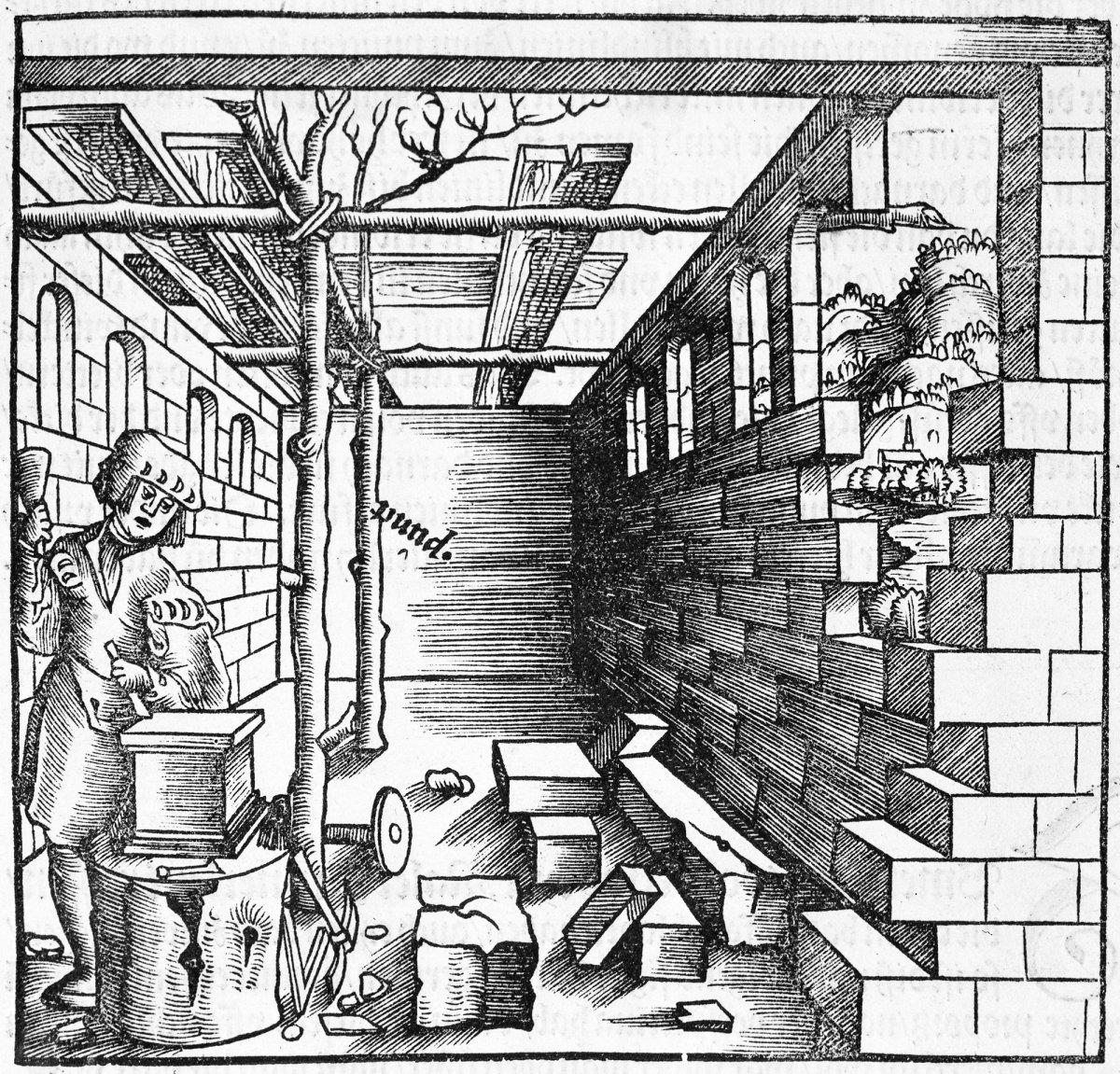

16th-century building site, Riba Collections

Developments in Britain

In Britain, as in much of Europe, its Renaissance came later than Italy’s but the idea of architecture as an intellectual pursuit of the upper classes was embraced. Italian architects were invited from overseas by the royal courts to add the latest flourishes to buildings but the craftsman-architect still persisted.

The housebuilding boom catalysed by the English Reformation and the division of former church land, reached its climax in the reign of Elizabeth I and saw the rise of the amateur architect - men of some status and education (often members of the clergy, aristocracy or minor nobility) - with an intellectual interest in practising architecture but usually with private sources of income. A patron might also act as his own architect, advised by specialist craftsmen and the architectural pattern books (with varying levels of accuracy) that were flooding the market at this time.

Alongside these independently wealthy men, there was the development of the role of semi-professional architect in the form of the master mason or craftsman who assisted these patrons with their designs. Robert Smythson is one of the most noted of these highly skilled designers working with Sir John Thynne at Longleat and Sir Francis Willoughby at Wollaton Hall. Slowly these transitional roles professionalised and the separate role of the professional architect emerged entirely distinct from either amateur or craftsman status. The craftsman-designer would however, continue to exist alongside the amateur architect in Britain until the second half of the 18th century.

The Great Fire of London in 1666 was to crystallise the new professional architect role. The sheer scale of rebuilding work required dedicated architects, like Christopher Wren, who was appointed King's Surveyor of Works in 1669. The architect moved from adviser to the client to overseer of the works and clients were compelled to find builders willing to work under the architect. This development forced the construction industry’s structure to change to something approaching the modern model.

This slow shift from medieval Europe to the 17th century adjusted the social hierarchy of construction. In the Middle Ages rival towns would compete for master masons in the way modern day football clubs compete for famous players. Their role, knowledge and skills were highly valued by medieval society.

The intellectualising of architectural theory in the Renaissance led, as we have seen, to the rise of the professional architect as a distinct role from construction. With the exception of aristocratic amateurs, architects had been seen as a sub-set of construction workers almost continuously since ancient Greece.

However, the combination of professional architect sitting in an overseer role, combined with the acceptance of architecture as a ‘learned’ art which could acceptably be practised by aristocrats, led to the implication that there was more social value in the intellectual side of architecture than the knowledge and craft of building. It was a slow but significant shift with consequences that are felt in industry tensions – and in the architecture we build – to this day.

The 19th century

By the early 1800s, we see yet more diversification of construction in the rampant demand created by a rapidly industrialising Britain and its growing Empire. A new role appeared for men with no connection or interest in architecture other than the purely financial.

Following the stock market crash of 1825, these men began to undertake construction work for others – subcontracting out the actual construction work and simply managing the process – in effect, ‘general contracting’ as it is now known. This led to a rapid drop in the perceived social value of building crafts as they became ‘subservient’ to this new role and a corresponding decrease in articled apprenticeships. Combined with the architect’s increasing remove from site, one of the results was a slow but steady decrease in build quality and a rise in profiteering behaviours.

The construction industry began to be seen as rife with fraud. Architects became such a byword for hypocrisy that Charles Dickens was able to satirise them in the character of Seth Pecksniff, the architect villain of his 1844 novel, Martin Chuzzlewit.

Ernest George and Peto, 1887 - Riba Collections

The founding of RIBA and the SPAB

In an attempt to protect their role and safeguard the profession by holding it to recognised standards, a group of architects formed what would become the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) in 1837. They insisted on a membership criterion that refused membership to those who had ‘any interest or participation in any trade or contract connected with building’.

In 1877, the designer, writer and architectural conservationist, William Morris and the architect and designer, Phillip Webb, co-founded the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings with a manifesto that responds directly to the industrialising construction industry. It calls for caution and craftsmanship in the care of old buildings and rails against the loss of historic fabric and the loss of building craft skills.

Philip Webb eschewed the opportunity to join the RIBA and on occasion chose to refer to himself as ‘a drains man’ – an acknowledgement perhaps, that he saw greater value in direct knowledge of building technology than the intellectual theory of architecture.

The evolving nature of the architect

Webb was in the minority however and the professionalising zeal of the RIBA architects won the day. Their lobbying eventually saw the architectural profession regulated with specific standards, codes of conduct and crucially, a defined education. Today ‘architect’ is a legally protected title in Britain.

The trend of the profession continued away from an understanding of building crafts and towards a more professional managerial role. The scale of reconstruction required after the World War II catalysed the growth of the construction industry and the nationalisation of much of the architectural services industry, pulling them ever further from their roots in construction. The belief at the time was that this demand and the importance of the work – in rebuilding cities and founding a welfare state – meant that architecture needed to attract the ‘best’ trainees.

Leaning heavily on the past century’s belief that architecture was a professional, intellectual art, this led to the raising of entry qualifications for architecture to degree level and the, I believe, illogical division of the profession into ‘architects’ and ‘architectural technicians’.

This separation, and the accompanying fracturing and specialisation of both design and construction did not solve the construction industry’s problems. To some extent, this change was necessary due to the growing scale, bureaucracy and complexity of many of Britain’s building projects. However, by the late 1980s there were government reports calling for greater collaboration and partnership across design, procurement and construction. Design and construction cannot exist without each other and to artificially sever them seems to have left us all the poorer. The SPAB works to remedy this through its Scholarship programme for early-career architects, but the entire industry should look for ways to bridge this continuing divide.

Eleanor Jolliffe is a practicing architect and co-author with Paul Crosby of Architect: the evolving story of a profession (RIBA, 2023).

This article originally appeared in the SPAB Magazine, a benefit of SPAB Membership.

Sign up for our email newsletter

Get involved