It's World Water Day. With so many drinking fountains falling into disrepair, Kathryn Ferry looks at how some authorities have reinstated them for the good of the community.

Not far from the SPAB office in Spital Square is a drinking fountain designed by founding architect Philip Webb. Located on Worship Street, it forms a corner detail at the east end of the terrace of artisan dwellings built by Webb from 1861-3.

These six properties replaced overcrowded slums, each one combining living accommodation, ground floor shop and rear workshop. Although the drinking fountain was unusual as a built-in feature it was very much in keeping with the socially improving ideals of the client and part of the drinking fountain movement that was gathering pace at that time.

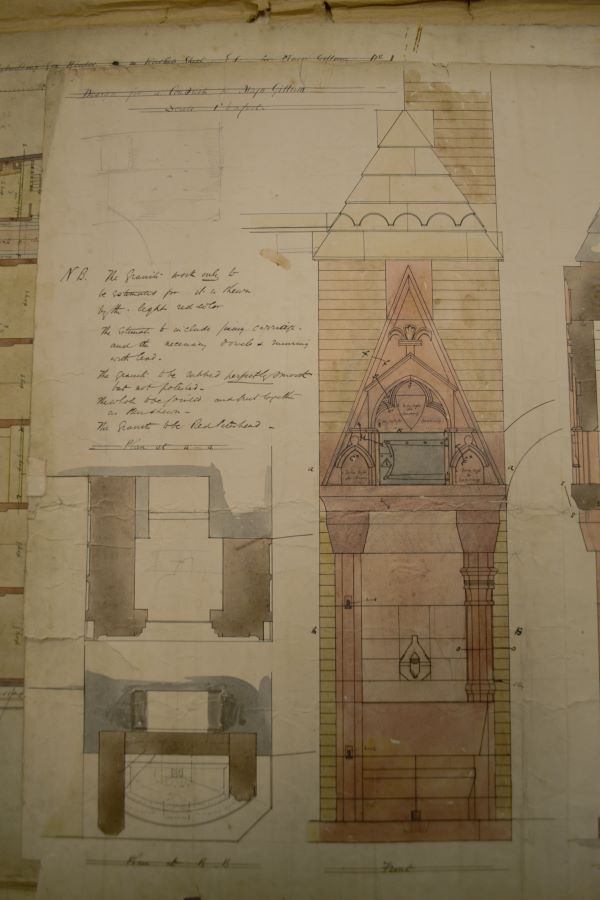

Webb’s drinking fountain is of characteristically simple design. Under a sharply pointed stone gable a granite basin fills the corner space, the weight of the wall above carried upon a polygonal column carved with a finely moulded capital (fig 1).

Drinking fountains elsewhere could be much grander, sometimes fancy to the point of excess, and appeared in a huge variety of different styles not to mention a range of materials from carved stone to cast iron and ceramic tiles. Many survive around the country, lots of them enjoy listed status but very few of them still actually provide any running water.

Water fountain, Worship Street. Credit: Mike Quinn.

Designs by architect Philip Webb. Credit: SPAB archive.

Since the 1960s and 70s pipes have been removed and taps taken away so that our historic drinking fountains have been reduced from functional infrastructure to mere street furniture. Whilst this transformation came about in response to the universal connection of British homes to mains drinking water, and in that respect represented a victory for public health, there is good reason to look anew at how these structures can be re-purposed to assist in cutting down our reliance on single-use plastic drinks bottles.

Though we take clean drinking water for granted now the lack of it caused serious problems for our Victorian forbears. Not only did thousands die every year from water borne diseases but inadequate supplies also drove hard-working labourers to quench their thirst at the pub or gin palace.

Temperance campaigners argued that this alcohol dependence led to crime and destitution so, unsurprisingly, they proved keen supporters of the drinking fountain movement. This began in Liverpool in 1854 when local philanthropist Charles Pierre Melly opened the first of his thirty drinking fountains, inspired by the examples he had seen on a visit to Geneva.

Places such as Leeds, Hull, Banbury, Preston and Derby followed suit and on 12 April 1859 the Metropolitan Free Drinking Fountain Association was established in London, to spread the benefits of clean water across the capital.

Drinking fountain inTorrington, Devon. Credit: Kathryn Ferry.

The Victorian building press published designs for and critiqued the wave of drinking fountains erected by public subscription and private donors. Many served a dual purpose as memorials to civic worthies and at each of Queen Victoria’s jubilees there was a new round of fountains put up in her honour. They often assumed the role of communal meeting point so the resemblance of pinnacled and crocketted Gothic designs to medieval market crosses was entirely conscious. Their location at road junctions meant, however, that many of these fountains were either demolished or moved when routes were changed in the twentieth century.

Unfortunately, it is far easier to find examples that have been conserved as ‘heritage assets’ rather than usable drinking fountains. One among the many stands to the west of St Woolos’ Cathedral in Newport, Gwent. It was presented to the town in 1913 by a former president of the British Women’s Temperance Association and is highly unusual for being manufactured in ceramic by Doulton of Lambeth. It was moved from Belle Vue Park in 1996 but its lack of function makes it a low priority for maintenance and a target for vandalism; the tiles are now in poor condition and the redundant basin is used as an ash tray.

Newport Doulton drinking fountain. Credit: Kathryn Ferry.

Since 2016 the Heritage of London Trust (HOLT) has been working to bring neglected fountains back into use. Its Director, Nicola Stacey, is concerned that council schemes have recently displayed an ‘alarming trend’ of pouring concrete into the bowls ensuring they are ‘permanently disfigured’.

HOLT experience has shown that just putting the taps back can have a massive aesthetic impact, helping to re-engender a sense of local pride in these structures. The best candidates for re-instatement are in public spaces with lots of passers-by where the trust can involve local communities throughout the conservation process.

At St Paul’s Recreation Ground in Brentford, school children were invited to watch the stone masons repairing the drinking fountain. A recent impact survey showed that 97% of those polled thought the park looked better following the work and 72% of people also felt it was safer. Most important of all, 94% of people had used the fountain to have a drink.

Conservation costs obviously differ but in the simplest cases it can cost under £20,000 including water connection and new taps. HOLT gives grants for drinking fountain projects in the capital and regularly advises local authorities and community groups. Fountain enthusiast Sebastian Bulmer uses his Instagram account to show the many Victorian examples ready and waiting to be renewed. On his travels he has discovered too many places where existing fountains have been so ignored that new ones have been installed right next door. Given a more joined-up approach, our historic drinking fountains could yet become shining beacons of sustainable heritage.

This article first appeared in the Autumn 2022 edition of the SPAB Magazine, a benefit of membership.